In the summer of 2016, two White House staffers -- Brian Mosteller and Joe Mahshie -- tied the knot in a rite led by one of America's most prominent Catholics.

The officiant was Vice President Joe Biden, who later proclaimed on Twitter: "Proud to marry Brian and Joe at my house. Couldn't be happier … two great guys."

Leaders of familiar Catholic armies then debated whether Biden's actions attacked this Catholic Catechism teaching: "The marriage covenant, by which a man and a woman form with each other an intimate communion of life and love, has been founded and endowed with its own special laws by the Creator. … Christ the Lord raised marriage between the baptized to the dignity of a sacrament."

Conflicts between bishops, clergy and laity will loom in the background as Biden seeks to become America's second Catholic president. Combatants will be returning to territory explored in a famous 1984 address by the late Gov. Mario Cuomo of New York, entitled "Religious Belief and Public Morality."

Speaking at the University of Notre Dame, he said: "As a Catholic, I have accepted certain answers as the right ones for myself and my family, and because I have, they have influenced me in special ways, as Matilda's husband, as a father of five children, as a son who stood next to his own father's death bed trying to decide if the tubes and needles no longer served a purpose.

"As a governor, however, I am involved in defining policies that determine other people's rights in these same areas of life and death. Abortion is one of these issues, and while it is one issue among many, it is one of the most controversial and affects me in a special way as a Catholic public official."

It would be wrong to make abortion policies the "exclusive litmus test of Catholic loyalty," he said. After all, the "Catholic church has come of age in America" and it's time for bishops to recognize that Catholic politicians have to be realistic negotiators in a pluralistic land.

Christian icons and art before the rise of the blue-eyed Jesus with blond hair

For modern skeptics, the 6th-century icon hanging in the Orthodox monastery in the shadow of Mount Sinai is simply a 33-by-18-inch board covered in bees wax and colored pigments.

For believers, this Christ Pantocrator ("ruler of all") icon is the most famous image of Jesus in the world, because the remote Sinai Peninsula location of St. Catherine's Monastery allowed it to survive the Byzantine iconoclasm era. The icon shows Jesus -- with a beard and long hair -- raising his right hand in blessing, while holding a golden book of the Gospels.

This Jesus does not have blond hair and blue eyes. "Christ of Sinai" shows the face of a wise teacher from ancient Palestine.

"When you talk about ancient icons, you are basically talking about images of Jesus with long hair, a beard and some kind of Roman toga. That's just about all you can say," said Jonathan Pageau of Quebec, an Eastern Orthodox artist and commentator on sacred symbols.

In the early church, he added, believers "didn't ask other questions -- about race and culture -- because those were not the important questions in those days. … Once you start politicizing icons there's just no way out of those arguments. You get into politics and dividing people and then you're lost."

In these troubled times, said Pageau, many analysts are "projecting valid concerns about racism and Europe's history of colonization and the plight of African-Americans back into issues of church history and art that are centuries and centuries old. It's a kind of category error and everything gets mixed up."

But that's what happened when debates about some #BlackLivesMatters activists toppling Confederate memorials -- along with attacks on Catholic statues and even insufficiently "woke" Founding Fathers -- veered into #WhiteJesus territory.

"Yes, I think the statues of the white European they claim is Jesus should also come down. They are a form of white supremacy," tweeted Shaun King, author of "Make Change: How to Fight Injustice, Dismantle Systemic Oppression, and Own Our Future."

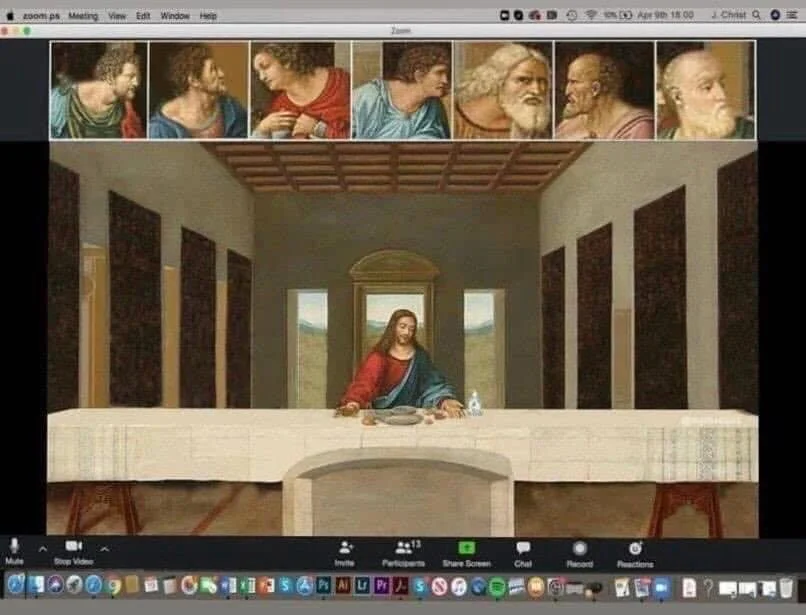

Anglican debate in 2020 crisis: Can clergy consecrate bread and wine over the Internet?

In the late 1970s, the Episcopal Ad Project began releasing spots taking shots at television preachers and other trends in American evangelicalism.

One image showed a television serving as an altar, holding a priest's stole, a chalice and plate of Eucharistic hosts. The headline asked: "With all due regard to TV Christianity, have you ever seen a Sony that gives Holy Communion?"

Now some Anglicans are debating whether it's valid -- during the coronavirus crisis -- to celebrate "virtual Eucharists," with computers linking priests at altars and communicants with their own bread and wine at home.

In a recent House of Bishops meeting -- online, of course -- Episcopal Church leaders backed away from allowing what many call "Virtual Holy Eucharist."

Episcopal News Service said bishops met in private small groups to discuss if it's "theologically sound to allow Episcopalians to gather separately and receive Communion that has been consecrated by a priest remotely during an online service."

Experiments had already begun, in some Zip codes. In April, Bishop Jacob Owensby of the Diocese of Western Louisiana encouraged such rites among "Priests who have the technical know-how, the equipment and the inclination" to proceed.

People at home, he wrote, will "provide for themselves bread and wine (bread alone is also permissible) and place it on a table in front of them. The priest's consecration of elements in front of her or him extends to the bread and wine in each … household. The people will consume the consecrated elements."

Days later, after consulting with America's presiding bishop," Bishop Owensby rescinded those instructions. "I understand that virtual consecration of elements at a physical or geographical distance from the Altar exceeds the recognized bounds set by our rubrics and inscribed in our theology of the Eucharist," he wrote.

However, similar debates were already taking place among other Anglicans. In Australia, for example, Archbishop Glenn Davies of Sydney urged priests to be creative during this pandemic, while churches were being forced to shut their doors.

During a live-streamed rite, he wrote, parishioners "could participate in their own homes via the internet consuming their own bread and wine, in accordance with our Lord's command."

Joe Biden and Democratic strategists face faith issues in 2020 that will not go away

It didn't matter where Pete Buttigieg traveled in Iowa and the early Democratic Party primaries -- voters kept asking similar questions.

Yes, they asked about his status as the first openly gay major-party candidate to hit the top tier of a presidential race. But they also wanted to know how his faith journey into the Episcopal Church affected his life and his take on politics.

"Those who are on my side of the aisle, those who view themselves as more progressive, are sometimes allergic to talking about faith in a way that I'm afraid has made it feel as if God really did have one political party," said Buttigieg, addressing a webinar for clergy and laypeople in his denomination's House of Deputies.

"It was very important to me to assert otherwise, but also to talk about the political implications of the commandments to concern ourselves with the well-being of the most marginalized and the most vulnerable and the idea that salvation has to do with standing with and for those who are cast out in society. … That energy carried the campaign, in ways that I never would have guessed."

But highly motivated religious believers are, of course, often divided by conflicts about doctrine that then spill over into politics.

Buttigieg waded into one such controversy during the campaign when candidate Beto O'Rourke said congregations and religious institutions that reject same-sex marriage should lose their tax-exempt status.

“If we want to talk about anti-discrimination law for a school or an organization, absolutely. They should not be able to discriminate," said Buttigieg, on CNN's State of the Union broadcast. "But going after the tax exemption of churches, Islamic centers or other religious facilities in this country, I think that's just going to deepen the divisions we are already experiencing."

Other Democrats face similar hot-button issues. Former vice president Joe Biden, during his fight over the "soul of the nation" with President Donald Trump, is sure to hear questions about his Catholic faith and his evolving beliefs on moral and political issues.

Biden backed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in 1993 and the Defense of Marriage Act in 1996. His views changed, while serving with President Barack Obama.

Pope John Paul II is a saint -- now some claim that it's time to add 'the great' to his title

As he began his 1979 pilgrimage through Poland, Pope John Paul II preached a soaring sermon that was fiercely Catholic, yet full of affection for his homeland.

For Communist leaders, the fact that the former Archbishop of Cracow linked faith to national pride was pure heresy. The pope joyfully claimed divine authority to challenge atheism and the government's efforts to reshape Polish culture.

"Man cannot be fully understood without Christ," John Paul II told 290,000 at a Mass in Warsaw's Victory Square. "He cannot understand who he is, nor what his true dignity is, nor what his vocation is, nor what his final end is. … Christ cannot be kept out of the history of man in any part of the globe, at any longitude or latitude of geography."

That was bad enough. Then he added: "It is therefore impossible without Christ to understand the history of the Polish nation. … If we reject this key to understanding our nation, we lay ourselves open to a substantial misunderstanding. We no longer understand ourselves."

This was the stuff of sainthood, and John Paul II received that title soon after his 26-year pontificate ended. But the global impact of that 1979 sermon is a perfect example of why many Catholics believe it's time to attach another title to his name -- "the great."

"The informal title 'the great' is not one that is formally granted by the church," explained historian Matthew Bunson, author of "The Pope Encyclopedia: An A to Z of the Holy See."

"Every saint who is also a pope is not hailed as 'the great,' but the popes who have been called 'the great' are all saints. … When you hear that title, you are dealing with both the love of the faithful for this saint and the judgement of history."

In the case of John Paul II, mourners chanted "Santo subito!" (Saint now!) and waved posters with that slogan at his funeral. During a Mass only 13 hours after his death, Cardinal Angelo Sodano spoke of "John Paul, indeed, John Paul the Great."

MIT chaplain learns that -- in these times -- mercy and justice are controversial subjects

Earlier this year, a Catholic priest published a book entitled "Mercy: What Every Catholic Should Know," focusing on doctrine and discipleship issues that, ordinarily, would not cause controversy.

But these are not ordinary times. Acting as a Catholic chaplain at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Father Daniel Moloney tried to apply his words about mercy and justice to the firestorm of protests and violence unleashed by the killing of George Floyd by a white Minneapolis police officer.

In the end, the priest resigned at the request of the Archdiocese of Boston, in response to MIT administration claims that Moloney, in a June 7 email, violated a campus policy prohibiting "actions or statements that diminish the value of individuals or groups of people."

Moloney wrote, in a meditation that defied simplistic soundbites: "George Floyd was killed by a police officer, and shouldn't have been. He had not lived a virtuous life. He was convicted of several crimes, including armed robbery. … And he was high on drugs at the time of his arrest.

"But we do not kill such people. He committed sins, but we root for sinners to change their lives and convert to the Gospel. Catholics want all life protected from conception until natural death."

Criminals have human dignity and deserve justice and mercy, the priest said. This is why Catholics are "asked to work to abolish the death penalty in this country."

On the other side of this painful equation, wrote Moloney, police officers struggle with issues of sin, anger and prejudice. Their work "often hardens them" in ways that cause "a cost to their souls." Real dangers can fuel attitudes that are "unjust and sinful," including racism.

In a passage stressed by critics, the priest wrote that the officer who knelt on Floyd's neck "until he died acted wrongly. … The charges filed against him allege dangerous negligence, but say nothing about his state of mind. … But he showed disregard for his life, and we cannot accept that in our law enforcement officers. It is right that he has been arrested and will be prosecuted.

"In the wake of George Floyd's death, most people in the country have framed this as an act of racism. I don't think we know that."

Waiting for a judicial 'Utah Compromise' on battles between religious liberty and gay rights?

No doubt about it, someone will have to negotiate a ceasefire someday between the Sexual Revolution and traditional religious believers, said Justice Anthony Kennedy, just before he left the U.S. Supreme Court.

America now recognizes that "gay persons and gay couples cannot be treated as social outcasts or as inferior in dignity and worth," he wrote, in the 2018 Masterpiece Cakeshop decision. "The laws and the Constitution can, and in some instances must, protect them in the exercise of their civil rights. At the same time, the religious and philosophical objections to gay marriage are protected views and in some instances protected forms of expression."

Kennedy then punted, adding: "The outcome of cases like this in other circumstances must await further elaboration in the courts."

The high court addressed one set of those circumstance this week in its 6-3 ruling (.pdf here) that employers who fire LGBTQ workers violate Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

Once again, the court said religious liberty questions will have to wait. Thus, the First Amendment's declaration that government "shall make no law … prohibiting the free exercise of religion" remains one of the most volatile flashpoints in American life, law and politics.

Writing for the majority, Justice Neil Gorsuch -- President Donald Trump's first high-court nominee -- expressed concern for "preserving the promise of the free exercise of religion enshrined in our Constitution." He noted that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 "operates as a kind of super statute, displacing the normal operation of other federal laws." Also, a 1972 amendment to Title VII added a strong religious employer exemption that allows faith groups to build institutions that defend their doctrines and traditions.

Nevertheless, wrote Gorsuch, how these various legal "doctrines protecting religious liberty interact with Title VII are questions for future cases too."

In a minority opinion, Justice Samuel Alito predicted fights may continue over the right of religious schools to hire staff that affirm the doctrines that define these institutions -- even after the court's 9-0 ruling backing "ministerial exemptions" in the Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School case in 2012.

Bad people, and good people, going to confession on movie screens -- for a century

Alfred Hitchcock knew a thing or two about complicated thrillers.

Having a murderer confess to a priest -- who couldn't betray this trust -- was already a familiar plot twist by 1953, when Hitchcock released "I Confess." Because of the seal of confession, this noble priest couldn't even clear his own name when police suspected that he was the killer.

Good prevails in the end. Shot by police, the killer makes an urgent final confession to the priest.

"It's natural for a Catholic filmmaker like Hitchcock to see the dramatic potential of confession, with its combination of mystery and holiness," said film critic Steven D. Greydanus, best known for his work for the National Catholic Register. "At the same time, Hitchcock thought 'I Confess' was a mistake, because he thought that his mostly Protestant audience in America just wouldn't get it."

The sacrament of confession is both sacred and secret -- facts known to Medieval playwrights as well as modern filmmakers. Thus, putting a confession rite on a movie screen is a "transgressive act" of the highest kind, said Greydanus, who serves as a permanent deacon in the Diocese of Newark, N.J. (Deacons do not hear confessions.)

"Voyeurism is an important theme in much of Hitchcock's work and he knew that using confession in this way was a kind of voyeurism. … He knew this was a kind of taboo."

Nevertheless, Hollywood scribes have frequently used confession and penance for everything from cheap laughs ("A League of Their Own"), to shattering guilt (Godfather III), to near-miraculous transformations ("The Mission"). In a recent 6,000-word essay -- "In Search of True Confession in the Movies" -- Greydanus covered a century of cinema, while admitting that he had to omit dozens of movies that included confession scenes.

The key is that filmmakers struggle to capture, in words and images, what is happening in a person's heart. The act of confession opens a window into the soul, since characters are forced to put their sins and struggles into words.

"Perhaps the very secrecy surrounding the sacrament of confession was part of what attracted filmmakers to depict it," wrote Greydanus.

Where is God in coronavirus crisis? Yes, that ancient question is part of this news story

Queen Elizabeth II has seen more than her share of good and evil during her 68 years on the British throne.

Candles shining in the darkness just before Easter are familiar symbols of the presence of good, even in the hardest of times, said the 92-year-old queen, in a recent address about a single subject affecting her people -- the coronavirus crisis.

"Easter isn't cancelled. Indeed, we need Easter as much as ever," she said. "The discovery of the risen Christ on the first Easter Day gave his followers new hope and fresh purpose, and we can all take heart from this. We know that coronavirus will not overcome us. As dark as death can be -- particularly for those suffering with grief -- light and life are greater."

An ancient question loomed over the queen's remarks: Where is God during this global pandemic that threatens the lives and futures of millions of people?

Theologians have a name -- "theodicy" -- for this puzzle. One website defines this term as "a branch of theology ... that attempts to reconcile the existence of evil in the world with the assumption of a benevolent God."

In his book "God in the Dock," the Christian apologist C.S. Lewis of Oxford University argued that "modern man" now assumes, when evil occurs, that God is on trial. This process "may even end in God's acquittal," he noted. "But the important thing is that Man is on the Bench and God is in the Dock."

This tension can be seen during news coverage of tragedies, wars, disasters and pandemics. Ordinary people involved in these stories often address "theodicy" questions, whether journalists realize it or not. This is a pattern I have observed many times -- since this past week marked my 32nd anniversary writing this national "On Religion" column.

The late Peter Jennings of ABC World News Tonight noted that, whenever news teams cover disasters, reporters often ask questions that sound like this: "How did you get through this terrible experience?" Survivors frequently reply: "I don't know. I just prayed. Without God's help, I don't think I could have made it."

What happens next, Jennings once told me, illustrates the gap that separates many journalists and most Americans. There will be an awkward silence, he said, and then the reporter will say something like: "That's nice. But what REALLY got you through this?"

Here we go again.